Data Structures (CSE 20312)

Prof. Jay Brockman, Fall 2025

2025-08-27

talked about unit tests and makefiles

in makefile:

- order does not matter! (uses algorithm that constructs dependency graph - topological sort)

- -g includes source code in compiled object file to allow for debugging

- -Wall is Warn all

The C Language!

- C (followed B) by Ken Thompson, Dennis Ritchie 1973

Memory Management

- utilization

- security

- ease of programing

- C exposes (and makes you deal with) details of memory

- Python (which we will use later) does not

sizeof(...) tells you how many bytes a datatype stores:

bool, char -- 1

short -- 2

int, float -- 4

double -- 8

int* , char* -- 8

2025-08-29

- 64 bit addresses sent from processor to memory

- 8 bit channel of data to go back and forth between processor and memory

(not entirely sure what is meant by this yet)

binary and hexadecimal numbers:

0 0000

1 0001

2 0010

3 0011

4 0100

5 0101

6 0110

7 0111

8 1000

9 1001

A 1010

B 1011

C 1100

D 1101

E 1110

F 1111

At each memory address you can only store one byte

- in most microprocessers, the least significant bit shows up in the lowest address in memory (little endian architecture)

- (over the air serially often sent as big endian)

Ex:

char c = 'A'; int x = 0xaabbccdd (0x denotes hexadecimal)

| name | address | value |

|---|---|---|

| c | ~ | 0x41 |

| (higher address) | 0xaa | |

| ~ | 0xbb | |

| ~ | 0xcc | |

| x | (lower address) | 0xdd |

pointer variables

int x = 1;

int *p; initializes start of 8 consecutive bytes in memory

p = &x sets p to x's address found in lookup table

*p = 5 changes the value at the address stored in p to 5

^ dereference * here is an operator, different than the one used to initialize pointer p

example in zybooks

#include <stdio.h>

int main()

{

int x = 5; // x, y are ints

int y = 1;

int *p; // p, q are addresses of ints

int *q;

p = &x; // p gets address of x

y = *p; // y gets value at address in p

printf("y = %d\n", y);

q = p; // q gets same address as p

printf("*p = %d *q = %d\n", *p, *q);

}

^ used debugger to watch values change step by step

Arrays are contiguous blocks of memory

int a; a <---value of a

int A[5]; A <---points to the starting value (A[0]) of the array

char char_v1;

int int_v1;

char char_v2;

int int_v2;

char char_array[4];

int int_array[4];

Address of char_v1: 0x7ffcd1389526

Address of int_v1: 0x7ffcd1389528

Address of char_v2: 0x7ffcd1389527

Address of int_v2: 0x7ffcd138952c

Address of char_array[0]: 0x7ffcd1389544

Address of char_array[1]: 0x7ffcd1389545

Address of int_array[0]: 0x7ffcd1389530

Address of int_array[1]: 0x7ffcd1389534

^ variables of same data type follow each other sequentially in memory

(i.e. by data type - not by order of declaration)

2025-09-01

pointer arithmetic

recap: arrays are contiguous blocks of memory

- array of chars one after the other

- array of ints need space for 4 bytes between each (each address holds 1 byte)

what happens when you add 1 to a pointer?

- increments by the sizeof the variable it points to (then points to the next

*(ptr + 3)<=>ptr[3]

pointers and strings

- a string is just a null-terminated array of chars

- (

0is the same as'\0')

char s[] = "abcde";

// _________________________________________________

// | 'a' | 'b' | 'c' | 'd' | 'e' | 0 |

// | &s[0] | &s[1] | &s[2] | &s[3] | &s[4] | &s[5] |

// -------------------------------------------------

cool trick we can do:

// Keep going while *(s + i) != 0 (false). (we could have also used s[i])

for (int i = 0; *(s + i); i++) {

printf("%c", *(s + i));

}

subtracting pointers

let char *p point to the '\0' in string s.

what is p-s?

- an int: the length of the string!

memory management

- most important part of system design!

Variables: have names (created by compiler)

Dynamic memory: doesn't have name, but has pointer to reach it (created at runtime)

Regions of Memory:

ffffffffffffffff

_________________

Stack (grows downward)

- contains function local variables

______ vv _______

______ ^^ _______

Heap (grows upward)

- from malloc, calloc, free

_________________ ^^ created at runtime (above)^^ vv (below) created at compile time vv

DATA FIXED SIZE

- contains global variables, static variables, constant strings

_________________

(Text) Code

- contains machine code to run program

_________________

0000000000000000

Heap: dynamic memory allocation in C

void *malloc(n_bytes)

- allocates n-bytes unitialized in memory

void *calloc(n_objects, bytes_per_object)

- allocates n-bytes of memory initialized to 0

free(void *ptr)

-

how does free know how much memory to free?

-

there must exist some table at runtime that keeps track of addresses allocated and how much!

-

actually a fairly complicated task to efficiently pack the heap

-

when you try to perform an operation on a segment/region in memory where you are not allowed to:

- segmentation fault!

-

growing the stack downward was a classic exploit in early computer systems for hackers to access/modify data and user code

What happens when you call a function?

void f3() {

// does something

}

void f1() {

// does something

}

void f2() {

f3();

}

void main() {

f1();

f2();

}

- Starts at top of stack

- Allocates stack frame for

main:

________ (TOP OF STACK)

| main |

-------- <-- stack pointer (points to the address below the top of the stack that has enough space for `main`'s variables)

- Allocates stack frame for

f1:

________ (TOP OF STACK)

| main |

--------

| f1 |

-------- <-- stack pointer

- f1 returns, now f2 stack frame is allocated in exact same location as f1 was

________ (TOP OF STACK)

| main |

--------

| f2 |

-------- <-- stack pointer

- f2 calls f3

________ (TOP OF STACK)

| main |

--------

| f2 |

--------

| f3 |

-------- <-- stack pointer

- returns all the way back

________ (TOP OF STACK)

| main |

-------- <-- stack pointer

- every time a function calls, it allocates a stack frame

- every time a function returns, it deallocates the stack frame

- does this by changing what's called the stack pointer

- (the code that allocates/deallocates the stack frame doesn't have to be written in C)

- in assembly, uses a register that is reserved to be your stack pointer

- you move the stack pointer, and then reference values relative to the stack pointer

"Isn't this exceedingly clever?"

Key part of computer system design: you don't want to waste memory!

The nature of functions calling functions automatically takes care of this for you with a stack

2025-09-03

call stack example

int add(int m, int n) {

m = m + n;

return m;

}

void square(int *a) {

*a = *a * *a;

}

int main() {

int x = 1;

int y = 1;

int z = add(x, y);

square(&z);

printf("x=%d y=%d z=%d\n", x, y, z);

return 0;

}

| name | address | value |

|---|---|---|

| y | 0x7...7e4 (highest in stack) | 1 |

| x | 0x7...7e0 | 1 |

| z | 0x7...7dc | 2, then 4 |

| m | 0x7...7bc | 1 |

| n | 0x7...7b8 | 1 |

| a | 0x7...7b8 (replaces n) | 0x7...7dc |

- when the stack frame of

addexpires, the stack frame ofsquarecan take its place - note how

a, which is a pointer of 8 bytes, replaces the address of n. This is because thesquarestack frame reallocated all eight bytes of the previous intsmandn(4+4 bytes) in order to storea. Because the byte order is little endian,astarts at the lower address, wherenpreviously started.

Data segment

--> has global variables, statics, and string constants

char a[] = "cat"; sizeof(a): 4

on main's stack frame:

_________________________________

| 'c' | 'a' | 't' | 0 |

---------------------------------

char *p = "dog"; sizeof(p): 8

"dog" is a string constant!

on main's stack frame:

_______________________________________________

| pointer p to data segment(8 bytes) |

-----------------------------------------------

in data segment:

_________________________________

| 'd' | 'o' | 'g' | 0 |

---------------------------------

We cannot do: p[0] = 'X'! It is a string constant that lives in the data segment.

note that global variables and static variables live in the data segment and can be written to

We can however reassign p to a different address: p = &a

But we cannot make an array point to a new address: a = p is illegal.

- Arrays are not pointer variables - they are fixed blocks of memory with a name (think compile-time alias to an address)

- In most expressions, the array name decays to a pointer to its first element (

&a[0]), but this is a value the compiler produces, not something stored that you can reassign.

2025-09-05

where do variables go in memory?

double GLOBAL = 3.14;

int main() {

int int_scalar = 25;

int int_array[] = {100, 101, 102, 103};

char *str_const = "hello";

int *malloc_array = malloc(10*sizeof(int))

static int static_int = 2;

- Stack:

&int_scalar,int_array,&str_const,&malloc_array - Heap:

malloc_array - Data:

str_const,&static_int,&GLOBAL - Code:

main

---------------------------stack----------------------------

int_array: 0x7ffc090b24d0, *int_array: 100

&malloc_array: 0x7ffc090b24c8, malloc_array: 0x652de1f3d2a0

&str_const: 0x7ffc090b24c0, str_const: 0x652dbe49b008

&int_scalar: 0x7ffc090b24bc, int_scalar: 25

----------------------------heap----------------------------

malloc_array: 0x652de1f3d2a0, *malloc_array: 0

----------------------------data----------------------------

&static_int: 0x652dbe49d018, static_int: 2

&GLOBAL: 0x652dbe49d010, GLOBAL: 3.140000

str_const: 0x652dbe49b008, *str_const: h

----------------------------code----------------------------

main: 0x652dbe49a1a9, *(unsigned char*)main: 0xf3 <- first opcode! (first byte of first instruction of main)

- mailbox -> contents analogy breaks down a bit for arrays -

arris not a box containing a pointer but more like a label for the whole row of boxes glued together. - It's just a design choice in C that when you use

arrin most expressions, the compiler treats it as the address of the first box (array decays to a pointer). You then use*or[]to access the individual values inside those "glued boxes".

I/O: printing strings:

char *string = "hello"

printf("%s\n", string);

puts(string); // only takes in strings; prints with a new line

reading input line by line

can use scanf, but we'll usually use fgets

char buffer[BUFSIZ]; // BUFSIZ is a constant defined in <stdio.h> (a couple thousand characters, more than enough)

while (fgets(buffer, BUFSIZ, stdin)) {

// process the buffer (maybe strdup into an array of strings)

}

small downside: fgets also captures newline \n. We can "chomp":

- Iterate through the buffer until you get to NULL character. If you encounter

\n, replace with\0and break.- e.g.

['c', 'a', 't', '\n', '\0']-->['c', 'a', 't', '\0', '\0'], which functionally is just['c' 'a' 't' '\0']

- e.g.

Arrays of strings

char** strarray: (i.e.(char*) *strarray)- use

callocto allocate an array of null pointers - use

strdupto allocate individual strings (e.g. from buffer) to each of those pointers

- use

_____

| * | strarray (on stack)

-----

| (points to first pointer in heap)

|

__V__

| * | - - >|'c'|'a'|'t'|'\0'| (each string also exists somewhere in heap, not necessarily in order among each other)

-----

| * | - - >|'d'|'o'|'g'|'\0'|

-----

| * | - - >|'m'|'o'|'u'|'s'|'e'|'\0'|

-----

To free this whole array of strings is sorta complicated:

- must first free strings individually, then free the pointers that pointed to those strings (everything exists on the heap except for the strarray pointer)

2025-09-08

reading user data into an array of strings (continuing from last class)

char **read_user_data(FILE *stream, int nstrings) {

char buffer[80]; // Up to 80 characters per string

char **sarray = calloc(nstrings, sizeof(char*)); // use calloc so that we have 0s at end to use as sentinel

int i = 0;

while (fgets(buffer, 80, stream)) {

chomp(buffer);

*(sarray+i) = strdup(buffer);

i++;

}

return sarray;

}

freeing a list of strings char** strarray

using free:

- delete each string

- delete each pointer

void free_string_array(char **sarray) {

for (int i = 0; sarray[i]; i++) {

free(sarray[i]); // free each individual string

}

free(sarray); // free the array of string pointers

}

Abstract Data Types (ADTs)

- a "big idea", defined by operations it supports

- internal details hidden from user

Today: Dynamic Array

Wednesday: Other ADTs on top of Dynamic Array (Stack, Queue, Set)

- ADTs are related to object oriented programming (but you don't need an object oriented programming language to implement ADTs)

review of structs:

Example: Point with x and y

struct Point {

int x;

int y;

};

nicer to do:

typdef struct {

int x;

int y;

} Point;

Point p; p.x = 1; p.y = 2;

| Label | Address | Value |

|---|---|---|

| (y) | Ox...F | 0x00 |

| (y) | Ox...E | 0x00 |

| (y) | Ox...D | 0x00 |

| start of y | Ox...C | 0x10 (2) |

| (x) | Ox...B | 0x00 |

| (x) | 0x...A | 0x00 |

| (x) | 0x...9 | 0x00 |

| p -> start of x | 0x...8 | 0x01 (1) |

- compiler typically pads struct size to power of 2

#include <stdio.h>

#include <stdlib.h>

#include <string.h>

typedef struct {

char *name;

int age;

} Person;

int main() {

// Declare a Person as a local variable

Person p;

p.name = "James";

p.age = 20;

// Allocate a Person on the heap

Person *p_ptr = malloc(sizeof(Person));

p_ptr->name = strdup("Madison");

p_ptr->age = 21;

printf("sizeof(p): %lu\n", sizeof(p)); // 16 (would have expected it to be 12 for char* and int)

printf("sizeof(*p_ptr): %lu\n", sizeof(*p_ptr)); // 16

free(p_ptr->name);

free(p_ptr);

}

Dynamic Array: Overview

- consists of an internal array that can grow dynamically

- need to keep track of:

- data array

- capacity

- size

____________

| data | ------> |__1__|__4__|__3__|_____|_____|

------------

| capacity | = 5 (how much total space in internal data array)

------------

| size | = 3 (number of elements stored within capacity)

------------

methods:

array_create()

- create new empty array

array_delete(Array *) - free an array and its contents

array_append(Array *, int value) - add an element to the end of the array (if full, reallocate to double capacity and copy over values if needed-e.g.)

array_at(Array *array, int index) - return the value at an index

array_index(Array *array, int value) - return the first index with a given value

array_insert(Array *array, int index, int value) - insert a new value at an index (and shifts elements after it to the right)

Growing an Array: realloc

void* realloc(void *p, size_t size) (size_t typically unsigned long int)

- takes in original array and new size (bytes)

- returns new array (with elements copied over)

Shifting elements to the right

|--[size]

v

|__31__|__32__|__33__|__35__|____|____|____|____|

^__want to insert(34, at index 3)

from: size

to: index

we set: data[i] = data[i-1]

Computational Complexity

space/time efficiency

Big O Notation

O(1): constant

O(N): proportional to N

O(N^2): proportional to N^2

...(covered more later)

Average (A) and Worst Case (W)

| Function | Time (A) | Time (W) | Space (A) | Space (W) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Append | O(1) | O(N) (realloc+copy) | O(1) | O(N) |

| At | O(1) | O(1) | O(1) | O(1) |

| Index | O(N) | O(N) | O(1) | O(1) |

| Insert | O(N) | O(N) | O(1) | O(N) (realloc) |

- Will get into the C code for Dynamic Arrays next class!

2025-09-10

- Abstraction: hiding detail and exposing the interface

Dynamic Array C code

array.h

#pragma once // (so that everything is included only once)

#include <stdbool.h>

#include <stdlib.h>

/* Constants */

#define ARRAY_DEFAULT_CAPACITY 1 << 2 // 4 elements

/* Structure */

typedef struct {

int *data; // Internal array

int capacity; // Total number of elements

int size; // Number of valid elements

} Array;

/* Functions */

Array* array_create();

void array_delete(Array *array);

void array_append(Array *array, int value);

int array_at(Array *array, int index);

int array_index(Array *array, int value);

void array_insert(Array *array, int index, int value);

array.c

#include "array.h"

#include <assert.h>

#include <string.h>

Array *array_create() {

// Allocate Array structure

Array *array = malloc(sizeof(Array));

// Initialize capacity and size

array->capacity = ARRAY_DEFAULT_CAPACITY;

array->size = 0;

// Allocate the data array

array->data = malloc(array->capacity * sizeof(int));

// return pointer to Array

return array;

}

void array_delete(Array *array) {

// Free the data array

free(array->data);

// Free the Array structure

free(array);

}

void array_append(Array *array, int value) {

// If the size is at capacity, double the capacity

if (array->size == array->capacity) {

array->capacity *= 2;

array->data = realloc(array->data, array->capacity * sizeof(int));

}

// Store value at end of array and increment size

array->data[array->size] = value;

array->size++;

}

int array_at(Array *array, int index) {

// Return the value at the index

return array->data[index];

}

int array_index(Array *array, int value) {

// Scan internal array for first element

// that matches value and return its index

for (int index = 0; index < array->size; index++)

if (array->data[index] == value) {

return index;

}

return -1; // Return -1 if no match found

}

void array_insert(Array *array, int index, int value) {

// If the size is at capacity, double the capacity

if (array->size == array->capacity) {

array->capacity *= 2; // Double the capacity

array->data = realloc(array->data, array->capacity * sizeof(int));

}

// Shift the values from index to the end of the array one element ahead

for (int i=array->size; i>index; i--) {

array->data[i] = array->data[i-1];

}

// Store new value and increment size

array->data[index] = value;

array->size++;

}

Stack: Overview

Push: add element to top

Pop: remove element from top

Top: peek at top

Empty: true if stack is empty

| |

| |

| 3 | <--Top of Stack

| 2 |

| 1 |

-----

Parentheses, Brackets, Braces Matching:

valid PBB Matching:

(){}[]

{[()]}

{}[]

invalid:

[)]

[{()]}

We can use the stack to write an algorithm to detect valid PBBs!:

traverse string in order left to right:

- push opening PBBs to stack

- if encounter a closing PBB, pop from stack and check if the popped opener matches the closer

for each input char c:

if c is an opener:

push c on stack

else:

if stack empty: return false

if c is closer that matches top:

pop stack

else:

return false

if stack is empty:

return true

else:

return false

2025-09-12

- using principles of object oriented programming to create

- abstraction (push and pop methods) and inheritance (stack "inherits" from dynamic array)

Implementing Stack, based on our previous implementation of Dynamic Array

stack.h

#pragma once

#include "array.h"

/* Structures */

typedef Array Stack;

/* Functions */

Stack* stack_create();

void stack_delete(Stack *stack);

void stack_push(Stack *s, int value);

int stack_pop(Stack *s);

int stack_top(Stack *s);

bool stack_empty(Stack *s);

stack.c

#include "stack.h"

#include <assert.h>

Stack* stack_create() {

return array_create();

}

void stack_delete(Stack *stack) {

array_delete(stack);

}

void stack_push(Stack *stack, int value) {

array_append(stack, value);

}

int stack_top(Stack *stack) {

assert(stack->size > 0);

return array_at(stack, stack->size - 1);

}

int stack_pop(Stack *stack) {

int top = stack_top(stack); // will assert false if stack is empty

stack->size--;

return top;

}

bool stack_empty(Stack *stack) {

return stack->size == 0;

}

Implementing Parentheses, Brackets, Braces Matching Algorithm:

#include <stdbool.h>

#include <stdio.h>

#include <stdlib.h>

#include <string.h>

#include "stack.h"

void chomp(char *str) {

size_t size = strlen(str);

if (*(str + size - 1) == '\n') *(str + size - 1) = 0;

}

bool is_pbb_matched(char *s) {

Stack *stack = stack_create();

for (char *c = s; *c; c++) {

// if char is an opener, push

if (*c == '{' || *c == '[' || *c == '(') {

stack_push(stack, *c); // push ascii value of opener

// else if char is a closer that match opener on stack, pop

} else if (!stack_empty(stack) &&

((*c == '}' && stack_top(stack) == '{') ||

(*c == ']' && stack_top(stack) == '[') ||

(*c == ')' && stack_top(stack) == '('))) {

stack_pop(stack);

// else no match

} else {

stack_delete(stack);

return false;

}

}

if (stack_empty(stack)) {

stack_delete(stack);

return true;

} else {

stack_delete(stack);

return false;

}

}

int main(int argc, char *argv[]) {

char buffer[BUFSIZ];

while (fgets(buffer, BUFSIZ, stdin)) {

chomp(buffer);

puts(is_pbb_matched(buffer) ? "pbb-matched" : "not pbb-matched");

}

return 0;

}

Stack vs. Queue

stack: Last In, First Out (LIFO)

___________________v---push and pop only on one end

|

--------------------

queue: First In, First Out (FIFO)

pop---v___________________v---push

(like a pipe!)

-------------------

methods for queue:

- push

- pop

- front

- empty

Complexity of Queue (implemented with a Dynamic Array):

| Function | Time (Avg) | Space (Avg) |

|---|---|---|

| Push | O(1) | O(1) |

| Pop | O(N) - have to shift everything | O(1) |

| Front | O(1) | O(1) |

| Empty | O(1) | O(1) |

deque (double ended queue):

push, pop--v_________________________________v---push, pop

(pipe that can flow either way)

---------------------------------

methods for queue:

- push left, push right

- pop left, pop right

- front

- empty

Set

- a "big bag of stuff" (unique, unordered stuff!)

methods: - add(value)

- contains(value)

- remove(value

Complexity of Set (implemented with a Dynamic Array):

| Function | Time (Avg) | Space (Avg) |

|---|---|---|

| Add | O(1) | O(1) |

| Contains | O(N) | O(1) |

| Remove | O(N) | O(1) |

Algorithm analysis

constant time operations: operations that take the same amount of time regardless of data value

- arithmetic operations

- variable assignments

- loops with fixed number of iterations

- indexing into an array

- comparisons

Big O Notation:

- IGNORE CONSTANTS

- if sum of terms, take the highest order term

- if product of terms, take the product of orders

Classic Big O Complexities:

O(1)

- array lookup and compare:

if a[i] == key

O(N)

- for loops:

for (i=0; i < size; i++) { do something O(1) }

O(N^2), and other polynomials

- typically nested for loops

for (i=0; i < size; i++) { do something O(N) }

O(log N)

- Divide and Conquer (e.g. binary search)

|__0__|__3__|__7__|__9__|__25__|__47__|__83__|

^--look at mid: > or < than key? (discard other half & repeat until mid==key)

- The most number of times we would need to cut in half is log_2(n)

- an array of 2^(20) elements would only take at most 20 steps to cut down to key

O(N log N)

- Divide into O(log N) subproblems, where each subproblem is O(N) to solve

- sorting algorithms can get to this speed

O(C^N), O(N!) - exponential, non-polynomial

- guessing a password by trying all combinations

2025-09-15

Comparing linear and binary search times

binary search is much faster!!

10,000 trials on sorted array of 2^(20) elements:

- 9.40 sec vs. 0.00115 sec

Some examples: what is their complexity?

example 1: dot products

O(N) because each element is multiplied and added pairwise

example 2: matrix multiplication

O(N^3)

for each row

for each column

take dot product - O(N)

example 3:

Euclidian GCD - greatest common divisor of a and b

(where N is bit length of a and b)

- Ensure that a is greater than b. If b is greater than a, swap the values of a and b.

- Computer the remainder of r of a divided by b

- If r is equal to 0, then the GCD of a and b is b. Otherwise, set a to b and b to r, and go back to step 2

- in terms of bit length, O(N) ~losing a bit of significance each time

- in terms of the magnitude of the numbers, O(log N) ~remainder is at most the difference between a and b

Recursion

- an algorithm that breaks a problem into subproblems and applies the algorithm itself

- needs a base case when can't subdivide further

Why recursion?

- useful for structures that are also recursive (like trees)

- lots of things can be seen as recursive! (e.g. arrays could be seen as unit element followed by array of length n-1)

- However, usually does not save time and space (particularly not space)

Basic recursive function:

recursive(data):

if (base case):

perform base action

return

else

recursive(reduced data)

Variants:

- sometimes return data value

- more than one base case

- more than one recursive call (e.g. recurse left, recurse right)

Examples:

- factorial

- cumulative sum

- print list reversed

- linear search

- binary search

- has duplicates

- reverse list

- fibonacci

int cumulative_sum(int n) {

if (n == 0) {

return 0;

}

return n + cumulative_sum(n-1);

}

int factorial(int n) {

if (n == 0) {

return 1;

}

return n * factorial(n - 1);

}

void print_string(char *s) { // "every string is a character followed by another string"

if (*s == '\0') {

putchar('\n');

return;

}

putchar(*s);

print_string(s+1);

}

2025-09-17

continuing recursion:

void reverse_array(int *list, int start_index, int end_index) {

if (start_index >= end_index) { // 0 or 1 elements left in middle

return;

}

// swap elements

int temp = list[start_index];

list[start_index] = list[end_index];

list[end_index] = temp;

reverse_array(list, start_index + 1, end_index - 1);

}

int linear_search(int *numbers, int high, int key) {

if (high < 0) {

return -1;

}

if (numbers[high] == key) {

return high;

}

return linear_search(numbers, high - 1, key);

}

int binary_search(int *numbers, int low, int high, int key) {

if (low > high)

return -1;

int mid = (low + high) / 2;

if (key > numbers[mid])

return binary_search(numbers, mid+1, high, key);

if (key < numbers[mid])

return binary_search(numbers, low, mid-1, key);

return mid;

}

bool has_duplicate(int *array, int high) {

if (high == 0)

return false;

if (linear_search(array, high-1, array[high]) >= 0)

return true;

return has_duplicate(array, high-1);

}

int fibonacci_number(int n) {

if (n == 0)

return 0;

if (n == 1)

return 1;

return fibonacci_number(n - 1) + fibonacci_number(n - 2);

}

Recurrence Relations

- look in book

- good review for discrete math, not going to cover extensively in this class

Recurrence relation for factorial:

(k)

|

(k)

|

(k)

|

... (repeated n times)

T(N) = k + T(N-1) => O(N)

Recurrence relation for has_duplicate:

(N)

|

(N-1)

|

(N-2)

|

... (repeated n times)

T(N) = N + T(N-1)

= N + N-1 + ... + 1 = (N+1)*(N/2) => O(N^2)

Sorting

2025-09-19

Bubble Sort

void BubbleSort(int *numbers, int numbersSize) {

for (int i = 0; i < numbersSize - 1; i++) {

for (int j = 0; j < numbersSize - i - 1; j++) {

if (numbers[j] > numbers[j+1]) {

int temp = numbers[j];

numbers[j] = numbers[j + 1];

numbers[j + 1] = temp;

}

}

}

}

// or...

void BubbleSort(int *numbers, int numbersSize) {

int i = numbersSize - 1;

while (i > 0) {

for (int j = 0; j < i; j++) {

if (numbers[j] > numbers[j + 1]) {

int temp = numbers[j];

numbers[j] = numbers[j + 1];

numbers[j + 1] = temp;

}

}

i--;

}

}

Insertion Sort

void InsertionSort(int *numbers, int numbersSize) {

for (int i = 1; i < numbersSize; ++i) {

int j = i;

// Insert numbers[i] into sorted part

// stopping once numbers[i] in correct position

while (j > 0 && numbers[j] < numbers[j - 1]) {

// Swap numbers[j] and numbers[j - 1]

int temp = numbers[j];

numbers[j] = numbers[j - 1];

numbers[j - 1] = temp;

--j;

}

}

}

Space Complexity

- Space complexity is how much ancillary space you need to allocate for the algorithm

- bubble sort and insertion sort both have O(1) space complexity

Adaptiveness and Stability

Adaptiveness: Takes advantage of partial sort

-

selection sort is not adaptive

-

insertion sort is adaptive (if array is already sorted, it would only need one pass)

-

bubble sort is not adaptive (always O(n^2))

-

we can modify bubble sort to make it adaptive

- keeps track of the last swap (if unable to make further swaps, we know everything after it must be sorted):

void BubbleSortImproved(int *numbers, int numbersSize) {

int last; // last swap index

for (int i = 0; i < numbersSize - 1; /* i updated below using last */) {

last = -1;

for (int j = 0; j < numbersSize - i - 1; j++) {

if (numbers[j] > numbers[j + 1]) {

int temp = numbers[j];

numbers[j] = numbers[j + 1];

numbers[j + 1] = temp;

last = j;

}

}

if (last == -1) break; // already sorted

i = numbersSize - last - 1; // shrink checked range

}

}

// or...

void BubbleSortImproved(int *numbers, int numbersSize) {

int i = numbersSize - 1;

while (i >= 1) {

int last = -1;

for (int j = 0; j < i; j++) {

if (numbers[j] > numbers[j+1]) {

int temp = numbers[j];

numbers[j] = numbers[j + 1];

numbers[j + 1] = temp;

last = j;

}

}

i = last;

}

}

We can also improve insertion sort (saves on write instructions):

void InsertionSortImproved(int *numbers, int numbersSize) {

for (int i = 1; i < numbersSize; i++) {

int j = i - 1;

int tmp = numbers[i];

while ((j >= 0) && (numbers[j] > tmp)) {

numbers[j+1] = numbers[j];

j = j - 1;

}

numbers[j+1] = tmp;

}

}

Stability: If two elements have the same the value, order will not be changed

- there may be additional information that would be messed up by switching order

- selection sort is not stable

- ex:

[2a, 2b, 1, 3, 4, 5]would go to[1, 2b, 2a, 3, 4, 5]

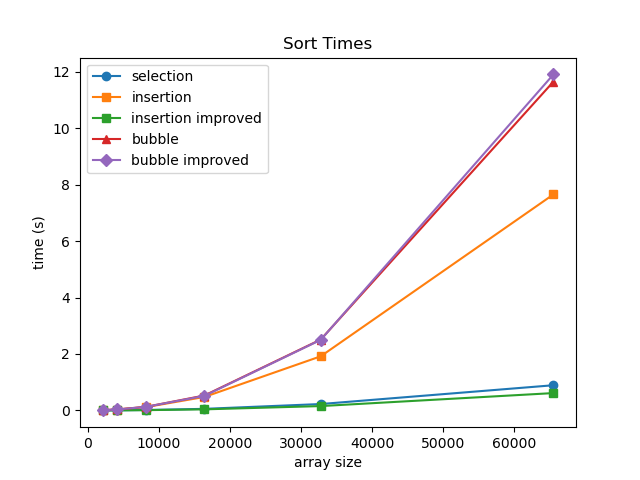

O(N^2) sorting algorithms build up sorted region through multiple passes

- Which is fastest (out of algorithms we have seen so far)?

- Let's test!

- Insertion sort (adaptive and stable; with enhancement is fastest)

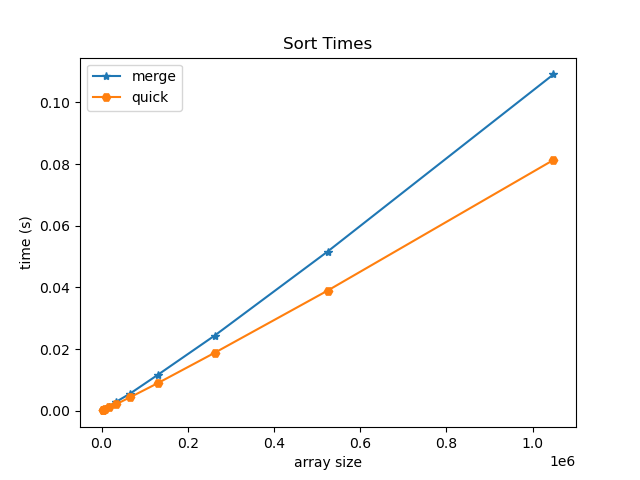

O(N log N) sorting algorithms build up a sorted order by dividing the problem and combining results.

Merge sort

did example in class physically sorting 16 people by first name using merge sort (cool!)

- start as individual

- merge into pairs

- merge pairs into new order (only comparing first of each pair)

- pair groups of 4 ... and so on ...(only comparing first of each order)

best, average, and worst time complexity: O(N log N)

space complexity: O(N) - need ancillary array of size N

Quicksort

average time complexity: O(N log N) - usually, depending on data/choices

average space complexity: O(log N) - auxiliary due to recursion stack

- partition array via swaps into regions above or below a pivot value

- pivot value can be chosen arbitrarily (first, last, middle, random, or median-of-three).

- small note: values in array equal to the pivot value can be in either partition (implementation-dependent)

- another note: we are not sorting around the pivot index - we are sorting around its value

- if we didn't use strict comparisons (> and <), the element from which we assigned the pivot can move

pivot_value = 4 (pick middle element)

|__3__|__6__|__1__|__4__|__7__|__2__|__5__|

^--low_index ^--high_index

while low_index <= high index:

increment low_index until array[low_index] > pivot_value

decrement high_index until array[high_index] < pivot_value

swap array[low_index] with array[high_index]

then, given ending position of low_index,

recursively apply sort on low partition (orig_low_index to ending_low_index)

recursively apply sort on high partition (ending_low_index+1 to orig_high_index)

Worst case: if pivots are always bad, it basically turns into selection sort

- time complexity: O(N^2)

- space complexity: O(N)

- example: pick pivot as lowest element, and array is already sorted

- website to visualize

- if we pass a sorted array to quicksort (picking pivot at index 0), you can visualize how it must recurse at every element (N times)

2025-09-22

Merge Sort Visualization

Quicksort & Merge Sort

Recap:

- bad pivot values => bad partitions => O(N^2) instead of O(N log N)

- merge sort is stable, quicksort is not

Merge Sort C code

#include <stdlib.h>

void Merge(int *numbers, int i, int j, int k) {

int mergedSize = k - i + 1; // Size of merged partition

int mergePos = 0; // Position to insert merged number

int leftPos = 0; // Position of elements in left partition

int rightPos = 0; // Position of elements in right partition

// Dynamically allocates temporary array for merged numbers

int *mergedNumbers = malloc(mergedSize * sizeof(int));

leftPos = i; // Initialize left partition position

rightPos = j + 1; // Initialize right partition position

// Add smallest element from left or right partition to merged numbers

while (leftPos <= j && rightPos <= k) {

if (numbers[leftPos] <= numbers[rightPos]) {

mergedNumbers[mergePos] = numbers[leftPos];

++leftPos;

}

else {

mergedNumbers[mergePos] = numbers[rightPos];

++rightPos;

}

++mergePos;

}

// If left partition is not empty, add remaining elements to merged numbers

while (leftPos <= j) {

mergedNumbers[mergePos] = numbers[leftPos];

++leftPos;

++mergePos;

}

// If right partition is not empty, add remaining elements to merged numbers

while (rightPos <= k) {

mergedNumbers[mergePos] = numbers[rightPos];

++rightPos;

++mergePos;

}

// Copy merge number back to numbers

for (mergePos = 0; mergePos < mergedSize; ++mergePos) {

numbers[i + mergePos] = mergedNumbers[mergePos];

}

free(mergedNumbers);

}

void MergeSort(int *numbers, int i, int k) {

int j = 0;

if (i < k) {

j = (i + k) / 2; // Find the midpoint in the partition

// Recursively sort left and right partitions

MergeSort(numbers, i, j);

MergeSort(numbers, j + 1, k);

// Merge left and right partition in sorted order

Merge(numbers, i, j, k);

}

}

| MERGE SORT | Time Complexity | Space Complexity |

|---|---|---|

| Best Case | O(N log N) | O(N) |

| Average Case | O(N log N) | O(N) |

| Worst Case | O(N log N) | O(N) |

| -- | ||

| Adaptive? | No | |

| Stable? | Yes |

side note: python uses Timsort, which essentially uses merge sort down to subarrays of 32 elements, and then uses insertion sort (which is adaptive)

Quicksort

#include <stdbool.h>

int Partition(int *numbers, int lowIndex, int highIndex) {

// Pick middle element as pivot

int midpoint = lowIndex + (highIndex - lowIndex) / 2;// avoids overflow, otherwise same as (highIndex + lowIndex) / 2;

int pivot = numbers[midpoint];

bool done = false;

while (!done) {

while (numbers[lowIndex] < pivot) {

lowIndex += 1;

}

while (pivot < numbers[highIndex]) {

highIndex -= 1;

}

// If zero or one elements remain, then all numbers are partitioned. Return highIndex.

if (lowIndex >= highIndex) {

done = true;

} else {

// Swap numbers[lowIndex] and numbers[highIndex]

int temp = numbers[lowIndex];

numbers[lowIndex] = numbers[highIndex];

numbers[highIndex] = temp;

// Update lowIndex and highIndex

lowIndex += 1;

highIndex -= 1;

}

}

// this will be the top of the low end for the next call

return highIndex;

}

void Quicksort(int *numbers, int lowIndex, int highIndex) {

// Base case: If the partition size is 1 or zero

// elements, then the partition is already sorted

if (lowIndex >= highIndex) {

return;

}

// Partition the data within the array. Value lowEndIndex

// returned from partitioning is the index of the low

// partition's last element.

int lowEndIndex = Partition(numbers, lowIndex, highIndex);

Quicksort(numbers, lowIndex, lowEndIndex);// recursively sort low partition

Quicksort(numbers, lowEndIndex + 1, highIndex);// recursively sort high partition

}

// from https://anim.ide.sk/sorting_algorithms_2.php

// Basically the same thing, may do one extra swap with itself

void Quicksort(int *a, int beg, int end) {

int i = beg;

int j = end;

int pivot = a[(i + j) / 2];

while (i <= j) { // i, j need to cross for next call

while (a[i] < pivot)

i++;

while (a[j] > pivot)

j--;

if (i <= j) {

// one last swap with yourself--no harm

int temp = a[i];

a[i] = a[j];

a[j] = temp;

i++;

j--;

}

}

if (beg < j)

Quicksort(a, beg, j);

if (i < end)

Quicksort(a, i, end);

}

| QUICKSORT | Time Complexity | Space Complexity |

|---|---|---|

| Best Case | O(N log N) | O(log N) |

| Average Case | O(N log N) | O(log N) |

| Worst Case | O(N^2) | O(N) |

| -- | ||

| Adaptive? | No | |

| Stable? | No |

Comparison:

NOTE: we did not cover radix sort in class, but may it be useful to review for interviews!

2 main data structure implementations:

- (dynamic) array based

- linked

Linked Data structures:

- linked lists

- trees

- graphs

For Recursive Data Structures:

- a child of a tree is a tree

- the rest of a list is a list

Linked Lists

made up of list nodes:

_________ _________

Value: | Blue | | Red |

--------- ---------

Next: | *---|--> | *---|--> null

--------- ---------

*Head-------^

first element in list we call the head

- head pointer lives in the stack

in class balloon demo: when inserting/removing elements, don't let go of any balloons! (memory leaks/dangling pointers)

insert node at head of list

Node *list_add_head(Node *head, int value) {

Node *n = malloc(sizeof(Node));

n->value = value;

n->next = head;

return n;

}

delete node from head of list

Node *list_remove_head(Node *head) {

Node *n = head;

head = n->next;

free(n);

return head;

}

2025-09-24

...continuing Linked Lists:

recap: when allocating variables on the heap, unless you maintain contact with them (using pointer), the balloon will float away (memory leak)!

Pointer Chasing (printing a linked list)

head --> [ ] --> [ ] --> [ ] --> 0

set n = head, move down the list!

void list_print_iterative(Node *head) {

for (Node *n = head; n != NULL; n = n->next) { // don't do n++! nodes are not sequential like arrays

printf("%d ", n->value);

}

printf("\n");

}

Adding node after current node

curr

↓

head --> [1] -x-> [3] --> [4] --> 0

↓ ↑

(malloc) n --> [2]

void list_add_after(Node *curr, int value) {

Node *n = malloc(sizeof(Node));

n->value = value;

n->next = curr->next;

curr->next = n;

}

Removing node after current node

curr successor

↓ (free!) ↓

head --> [1] -x-> [3] --> [4] --> 0

↓ ↑

-->-->-->-->-->--^

void list_remove_after(Node *curr) {

Node *successor = curr->next->next;

free(curr->next);

curr->next = successor;

}

Print list recursively

void list_print_recursive(Node *head) {

if (head == NULL) {

printf("\n");

return;

}

printf("%d ", head->value);

list_print_recursive(head->next);

}

void list_print_reversed_recursive(Node *head, Node *curr) {

if (curr == NULL) {

return;

}

list_print_reversed_recursive(head, curr->next); // recurse _before_ we print

printf("%d ", curr->value);

if (curr == head) printf("\n"); // same head is passed to every recursive call

}

// called as: list_print_reversed_recursive(head, head);

Deleting a Linked LIst

void list_delete_iterative(Node *head) {

while (head != NULL) {

Node *n = head;

head = head->next;

free(n);

}

}

void list_delete_recursive(Node *head) {

if (head == NULL) {

return;

}

list_delete_recursive(head->next); // recurse first!

free(head);

}

Stack implemented using Linked List

recall:

- when using Dynamic Arrays for stacks, we pushed/popped at the end of the array.

- otherwise we would have had to shift elements - O(N)

for linked lists:

- we push/pop at the head - O(1)

- otherwise pushing/popping at the tail requires O(N) traversal

Queue using a Linked List

- because we push at one end and pop at the other end, one operation will have to be O(N)

- but what if we add a tail?

tail (push only)

↓

head --> [ ] --> [ ] --> [ ] --> [ ] --> 0

- then, we can push to the tail and pop from the head

- NOTE: we cannot pop from the tail, because we cannot cannot look backwards!!!

- this brings us to doubly linked lists...

2025-09-26

Queue using Linked list

recap:

- insert at tail & remove at head (easy)

- insert at head & remove at tail (hard - we can't see backwards!)

- we need prev pointers if we want both operations at tail

- therefore...

Deque (double ended queue) using Doubly-Linked List

- each note contains next and prev:

(head) (tail)

_________ _________ _________

Value: | Blue | | Red | | Green |

--------- --------- ---------

Next: | *---|--> | *---|--> | *---|--> null

--------- --------- ---------

Prev: null <--|---* | <--|---* | <--|---* |

--------- --------- ---------

- aside: one of the few places that python uses doubly-linked lists is for its implementation of deque

- queues aren't generally used for large amounts of data (too much auxiliary space)

- limitation/awkwardness of linked lists: need to check boundary conditions (is_empty, adding/removing head or tail)

- solution: Doubly-linked list with dummy elements

- now:

head->nextrefers to first element in list,tail->prevrefers to the last

head tail

↓ ↓

[dummy] <-> [10] <-> [20] <-> [30] <-> [dummy]

Doubly Linked List Implementation

#include <stdio.h>

#include <stdlib.h>

// Definition of a Node

typedef struct Node {

int data;

struct Node* prev;

struct Node* next;

} Node;

// Definition of a Doubly Linked List

typedef struct DoublyLinkedList {

Node* head; // Dummy head

Node* tail; // Dummy tail

} DoublyLinkedList;

// Create a new node

Node* create_node(int data) {

Node* new_node = (Node*)malloc(sizeof(Node));

new_node->data = data;

new_node->prev = new_node->next = NULL;

return new_node;

}

// Initialize the doubly linked list with Dummy nodes

DoublyLinkedList* create_list() {

DoublyLinkedList* list = (DoublyLinkedList*)malloc(sizeof(DoublyLinkedList));

list->head = create_node(0); // Dummy head

list->tail = create_node(0); // Dummy tail

list->head->next = list->tail;

list->tail->prev = list->head;

return list;

}

// Check if the list is empty

int is_empty(DoublyLinkedList* list) {

return list->head->next == list->tail;

}

// Helper function: Insert node after current node

void insert_after(Node *current, int data) {

Node* new_node = create_node(data);

Node* next_node = current->next;

current->next = new_node;

new_node->prev = current;

new_node->next = next_node;

next_node->prev = new_node;

}

// Helper function: Remove current node and return data

int pop(Node* current) {

int data = current->data;

current->prev->next = current->next;

current->next->prev = current->prev;

free(current);

return data;

}

// Prepend an element to the head of the list

void prepend(DoublyLinkedList* list, int data) {

insert_after(list->head, data);

}

// Append an element to the tail of the list

void append(DoublyLinkedList* list, int data) {

insert_after(list->tail->prev, data);

}

// Remove the (non-dummy) head of the list and return value

int pop_head(DoublyLinkedList* list) {

return pop(list->head->next);

}

// Remove the (non-dummy) head of the list and return value

int pop_tail(DoublyLinkedList* list) {

return pop(list->tail->prev);

}

// Insert an element at a specific position (0-based index)

void insert_at(DoublyLinkedList* list, int data, int position) {

Node* current = list->head;

int i = 0;

// Traverse the list to find the position

while (current->next != list->tail && i < position) {

current = current->next;

i++;

}

insert_after(current, data);

}

// Delete an element at a specific position (0-based index)

void delete_at(DoublyLinkedList* list, int position) {

Node* current = list->head->next; // Start from the first valid node

int i = 0;

// Traverse to the node at the specified position

while (current != list->tail && i < position) {

current = current->next;

i++;

}

// If we are at a valid node (not the Dummy tail)

if (current != list->tail) {

pop(current);

}

}

// Delete an element by value

int delete_by_value(DoublyLinkedList* list, int data) {

Node* current = list->head->next; // Start from the first valid node

while (current != list->tail) {

if (current->data == data) {

pop(current);

return 1; // Data found and deleted

}

current = current->next;

}

return 0; // Data not found

}

// Display the list forward

void display_forward(DoublyLinkedList* list) {

printf("Head <-> ");

Node* current = list->head->next; // Start from the first valid node

while (current != list->tail) {

printf("%d <-> ", current->data);

current = current->next;

}

printf("Tail\n");

}

// Display the list backward

void display_backward(DoublyLinkedList* list) {

printf("Tail <-> ");

Node* current = list->tail->prev; // Start from the last valid node

while (current != list->head) {

printf("%d <-> ", current->data);

current = current->prev;

}

printf("Head\n");

}

// Free the memory allocated for the list

void free_list(DoublyLinkedList* list) {

Node* current = list->head;

while (current != NULL) {

Node* next = current->next;

free(current);

current = next;

}

free(list);

}

Note: we can actually implement doubly linked list with a single dummy node (this is how python implements deque)

- becomes like a circle, where

dummy->nextis the head, and,dummy->previs the tail

2025-09-29

recap: doubly linked lists - dummy nodes aren't necessary but are helpful for avoiding extra checks

Employee Record Database

Employee Record object (struct)

- Number id (int)

- Name (string)

Operations:

- insert

- lookup by id

if implemented using dynamic array, lookup is O(N) if unsorted, else O(log N)

what if we use the employee id as the index?

[name][name][name][name] ... [name]

0 1 2 3 9999

Now, lookup is O(1), but we need to use a massive array!

solution: use "buckets" instead of single name string per index

|__| |__| |__| |__| ... |__|

|__| |__| |__| |__| ... |__|

|__| |__| |__| |__| ... |__|

0 1 2 3 999

^ instead of indexing by id, index by last 3 elements of id!

- each bucket points to a linked list (we call this chaining, essentially an array of linked lists)

- hash function: take last 3 digits of id (id MOD 1000, id % 1000)

Now, suppose we wanted to lookup people by name to get id?

- key is now a string instead of a number -- how do we index? i.e. what is our new hash function?

- ideas:

- use first letters of last name

- 1 letter:

26buckets - 2 letters:

26^2buckets - 3 letters:

26^3buckets

- 1 letter:

- take sum of ascii values

- 5 letter words:

5*26 = 130buckets

- 5 letter words:

- use first letters of last name

- ideas:

A good hash function:

- Doesn't reduce info much

- ex: not ideal to reduce 26^5 possible 5 letter words into 130 buckets

- Maintains randomness

Load factor of a hash table

Def: number of records (size) / the capacity (# of buckets)

ex:

|__|

null |__| |__| null

0 1 2 3

load factor = 3/4 = 0.75

Alpha (α): when load factor is greater than α, triggers resizing & rehashing of hash table

- ex: if α = 0.5, the example above would trigger resizing

Pair Structure

typedef struct {

char *key;

int value;

Pair *next;

} Pair;

Table Structure

typedef struct {

Pair **buckets;

int capacity;

int size;

} Table;

Pair functions

#include "pair.h"

#include <stdlib.h>

#include <string.h>

Pair *pair_create(const char *key, int value, Pair *next) {

Pair *p = calloc(1, sizeof(Pair));

p->key = strdup(key);

p->value = value;

p->next = next;

return p;

}

void pair_delete(Pair *p) {

if (!p) return;

pair_delete(p->next);

free(p->key);

free(p);

}

Basic Hash Function (sum of ascii values)

int hash(char *str) {

int value = 0;

for (int i = 0; str[i] != '\0'; i++) {

value += str[i];

}

return value;

}

Table functions

#include "table.h"

#include "hash.h"

#include <stdio.h>

#include <string.h>

Table *table_create() {

Table *t = calloc(1, sizeof(Table));

t->capacity = TABLE_DEFAULT_CAPACITY;

t->buckets = calloc(t->capacity, sizeof(Pair *));

return t;

}

void table_delete(Table *t) {

for (int bucket = 0; bucket < t->capacity; bucket++) {

pair_delete(t->buckets[bucket]);

}

free(t->buckets);

free(t);

}

int table_lookup(Table *t, char *key) {

int bucket = hash(key) % t->capacity;

// look for the key in the bucket's chain of pairs and return value if you find it.

for (Pair *p = t->buckets[bucket]; p != NULL; p = p->next) {

if (strcmp(p->key, key) == 0) {

return p->value;

}

}

return -1; // key is not found

}

void table_insert(Table *t, char *key, int value) {

if (table_lookup(t, key) != -1) {

return;

}

// inserts a pair at the head of the bucket's chain

int bucket = hash(key) % t->capacity;

t->buckets[bucket] = pair_create(key, value, t->buckets[bucket]);

t->size++;

}

void table_print(Table *t) {

for (int bucket = 0; bucket < t->capacity; bucket++) {

printf("Bucket %d: ", bucket);

for (Pair *curr = t->buckets[bucket]; curr; curr = curr->next)

printf(" {%s: %d}", curr->key, curr->value);

printf("\n");

}

}

2025-10-01

what if we don't want to use linked lists in each bucket?

Linear Probing

- if there is a collision, continue down the hash table until there is an empty bucket

Hash table: Want to insert 11, 19, 30, 15, 22

|___|___|___|___|___|___|___|___|

0 1 2 3 4 5 6 7

|_22|___|___|_11|_19|___|_30|_15|

0 1 2 3 4 5 6 7

^--bucket 3 was already full

^--buckets 6&7 were full (loops around)

-

note that we must distinguish between buckets that are

empty-since-startandempty-after-removal:- when searching, we start at the index given from the hash

- then, we continue until we find the key or reach an

empty-since-startbucket - Note also that items may be inserted in buckets that are either

empty-since-startorempty-after-removal.

-

also notice that when probing (for search, insert, or remove), we must:

- keep a count to only probe up to N times, where N is the hash table's size

- use

bucket = (bucket + 1) % Nto increment bucket index, because the index can wrap around

-

sometimes quadratic probing is used because it can lead to fewer collisions

-

later: lots of good optional pages on the zybooks to check out (on sorting, hashing, etc.)

Collisions and Hashing

Hash table: Want to insert 2, 10, 18

|___|___|_*_|___|___|___|___|___|

0 1 2 3 4 5 6 7

-

using mod 8, they all map to bucket 2!

-

idea: want to take keys and make them as random as possible

-

solution: multiply key by a large random number (

abdefg * xyz)- intuitively, each partial product of each digit (x, y, z) added together feels pretty random (especially taking middle bits)

story about Fred Warren's calculating machine and demo of a 1920s Thales calculator

what number abdefg do we choose?

- e.g.,

1000000would be a very bad choice - using very large prime numbers work well

- or, use one less than a large power of 2

Fast Hashing: Shift and add

- shifting to the left is the same as multiplying by 2

multiplying x by 33 is same as(x*32) + xis the same as(x << 5) + x

String hash

djb2 - Daniel J. Bernstein

unsigned long hash(unsigned char *str) {

unsigned long hash = 5381;

int c;

while (c = *str++)

hash = ((hash << 5) + hash) + c; // hash = hash * 33 + c

return hash;

}

Comparing hash functions

- mid square hash: multiplies by itself, takes middle bits

- Donald Knuth's hash: multiplies by "weird" number, takes middle bits

table index: 4 bits

table size: 16 buckets

all keys collide on bin: 1

key key^2 binary key^2 mid-square knuth

1 1 1 0 9

17 289 100100001 8 8

33 1089 10001000001 8 6

49 2401 100101100001 6 4

65 4225 1000010000001 8 2

81 6561 1100110100001 10 0

97 9409 10010011000001 6 15

113 12769 11000111100001 15 13

129 16641 100000100000001 8 11

Note:

- Say we extract R digits from the result's middle, and return the remainder of the middle digits divided by hash table size N:

- For N buckets, R must be greater than or equal to log(N) to index all buckets

- (where log is base 2, or base 10, etc. depending on the base of the digits we extract)

- we usually use binary because getting the middle bits is fast

How many buckets?

- zybook says to use prime number of buckets

- convention is to use a power of 2 (easy to use) and then just trust hash function

2025-10-03

- last topic on exam is doubly-linked lists with dummy elements

Moving from C to Python

Recall: C dynamic Array

typedef struct {

int *data; // Internal array

int capacity; // Total number of elements

int size; // Number of valid elements

} Array;

/* Functions */

Array* array_create();

void array_delete(Array *array);

void array_append(Array *array, int value);

int array_at(Array *array, int index);

int array_index(Array *array, int value);

void array_insert(Array *array, int index, int value);

array_createis our "constructor"array_deleteis our "destructor"- notice how each method has to be given an

Array *arrayas an argument! - additionally,

array_is used a a prefix to our methods only out of convention

C++ implementation (object-oriented extension from C):

class Array {

private:

int *data

int capacity

int size

public:

Array(); // constructor

~Array(); // destructor

void append(int value);

int at(int index) const;

int index_of(int value) const;

void insert(int index, int value);

int get_size() const;

}

int main() {

Array arr;

arr.append(10);

arr.append(20);

arr.insert(1, 15);

std::cout << "arr[1] is " << arr.at(1) << std::endl;

std::cout << "Value 20 is at index " << arr.index_of(20) << std::endl;

return 0;

}

Abstraction

Def: hiding private implementation details and exposing a public interface through methods

Inheritance

Def: Child class takes methods and attributes from parent

- ex: Shape class might contain

Shape.draw_fill()orShape.position- child classes, e.g.

Circle, Square, Pentagonmight have similar characteristics

- child classes, e.g.

Polymorphism

Def: type-specific methods with the same name

- ex:

Shape.calc_perimeter()would want to be implemented differently depending on the child class

Python built-in types

<class 'int'> <class 'float'> <class 'str'> <class 'list'> <class 'set'> <class 'dict'> <class 'tuple'>

- Unlike C, the types of variables in Python are determined on the fly based on the values assigned to them

- C is "statically typed", Python is "dynamically typed"

- Everything in Python is an object!!!

- all classes (including built-ins like

int,list, etc.), ultimately inherit from the built-inobjecttype.

- all classes (including built-ins like

- According to its type, every object has a set of methods that apply to it.

- the function

dir()returns a list of all methods of an object.

- the function

Magic methods

- Regular methods have "regular" names and are called by adding a dot and the method name to the name of an object.

- Magic methods have "magic" names that begin and end with a double underscore ("dunder").

- can be called in the same manner as regular methods

- but are "magic" because they can be called by Python language keywords and operators.

- some examples:

__eq__implements=="hello".__eq__("goodbye")is the same as"hello" == "goodbye"(both False)__contains__can be invoked usinginkeyword

Listing of methods for Python base object (from which all objects inherit!):

['__class__', '__delattr__', '__dir__', '__doc__', '__eq__', '__format__', '__ge__', '__getattribute__', '__gt__', '__hash__', '__init__', '__init_subclass__', '__le__', '__lt__', '__ne__', '__new__', '__reduce__', '__reduce_ex__', '__repr__', '__setattr__', '__sizeof__', '__str__', '__subclasshook__']

Looking at CPython!

List implementation:

listobject.c

- notice how their resize function is less aggressive than the doubling we did

Set implementation:

setobject.c

- check out the hash implementation!

From listsort.txt:

Intro

-----

This describes an adaptive, stable, natural mergesort, modestly called

timsort (hey, I earned it <wink>). It has supernatural performance on many

kinds of partially ordered arrays (less than lg(N!) comparisons needed, and

as few as N-1), yet as fast as Python's previous highly tuned samplesort

hybrid on random arrays.

In a nutshell, the main routine marches over the array once, left to right,

alternately identifying the next run, then merging it into the previous

runs "intelligently". Everything else is complication for speed, and some

hard-won measure of memory efficiency.

Some recommended resources:

w3schools.com

tutorialspoint.com

realpython.com

docs.python.org

2025-10-06

Review for Midterm Exam

Know your powers of 2!

2^0 = 1

2^1 = 2

2^2 = 4

2^3 = 8

2^4 = 16

2^5 = 32

2^6 = 64

2^7 = 128

2^8 = 256

2^9 = 512

2^10 = 1024 (roughly 10^3)

...

2^20 = 1,048,576 (roughly 10^6)

2^30 = 1,073,741,824 (roughly 10^9)

2^40 = 1,099,511,627,776 (roughly 10^12)

Every 10 powers of 2 is roughly 3 powers of 10

- i.e., Every 10 doublings is about a thousand times bigger

- (because 1024=2^10 is roughly 1000=10^3)

To find other powers, use nearest multiple of 10:

2^15 = (2^10)(2^5) = roughly 32000 (actually 32768)

2^23 = (2^20)(2^3) = roughly 8 million (actually 8388608)

2^25 = (2^20)(2^5) = roughly 32 million (actually 33554432)

2^32 = (2^30)(2^2) = roughly 4 billion (actually 4294967296)

Storage Reference:

- 1 KB = 2^10 bytes

- 1 MB = 2^20 bytes

- 1 GB = 2^30 bytes

- 1 TB = 2^40 bytes

Recall: Regions of Memory

int p = 3

int main() {

int i = 25;

char a[] = "wx";

char *s = "yz";

int *m = malloc(10 * sizeof(int));

static int t = 2;

*m = 100;

*(m + 1) = 101;

m[2] = 103;

}

Assume 6-bit memory address: 0x00 - 0x3F (0-63)

Assume each memory location has enough bits to hold an int, char, or address

| STACK | HEAP | DATA | CODE |

|---|---|---|---|

3F: i: 25 |

2F: | 1F: | 0F: |

3E: '\0' |

2E: | 1E: | 0E: |

3D: 'x' |

2D: | 1D: | 0D: |

3C: a: 'w' |

2C: | 1C: | 0C: |

3B: s: 0x11 |

2B: | 1B: | 0B: |

3A: m: 0x20 |

2A: | 1A: | 0A: |

| 39: | 29: | 19: | 09: |

| 38: | 28: | 18: | 08: |

| 37: | 27: | 17: | 07: |

| 36: | 26: | 16: | 06: |

| 35: | 25: | 15: | 05: |

| 34: | 24: | 14: t: 2 |

04: |

| 33: | 23: | 13: '\0' |

03: |

| 32: | 22: 103 |

12: 'z' |

02: |

| 31: | 21: 101 |

11: 'y' |

01: |

| 30: | 20: 100 |

10: p: 3 |

00: main: *m = 100 |

remember, in reality, usually:

- size of a data word at each address is 1 byte (8 bits)

- chars are 1 byte

- ints are 4 bytes

- addresses are 8 bytes

in-class activity: Kahoot!

2025-10-08

Midterm Exam

2025-10-10

Running Python in VSCode

python3 first_script.py

if python file contains #!/usr/bin/env python3 at the top:

chmod +x first_script.py

./first_script.py

Use the VS Code debugger

- Set a breakpoint in your program

- Click the debugger icon in the sidebar

- Click Run and Debug (no need for a launch.json file)

- Select Python Debugger (only need to set this the first time)

- Select Python File Debug the currently active Python file as the configuration (only need to set this the first time)

Tip: If you want to set a breakpoint where there isn't conveniently a line to stop on, such as at the very end of a script, you can add a pass statement.

basic python stuff

# Adding two numbers

x = 5

y = 10

z = x + y

print(z)

# Adding two strings

x = "Hello"

y = "World"

z = x + " " + y

print(z)

# Formatting strings (f-strings)

x = 75

y = 25

z = f"The sum of {x} and {y} is {x + y}"

print(z)

# While loop and if statement

x = 0

while x < 5:

if x % 2 == 0:

print(x)

x += 1

# For loop

# Note: range(5) only goes up to 4

for x in range(5):

if x % 2 == 0:

print(x)

# list

x = [100, 200, 300, 400, 500]

x.append(600)

x[2] = 350

# for loop with list

for y in x:

print(y)

# slicing a list

# Note: x[1:3] only includes elements at index 1 and 2

y = x[1:3]

print(y)

y = x.pop(0)

print(y)

# dictionary

x = {"a": 100, "b": 200, "c": 300}

x["d"] = 400

x["a"] = 150

if ("a" in x):

print("Key 'a' exists")

# set

x = set()

x.add(100)

x.add(200)

x.add(300)

x.remove(200)

print(x)

Unit Testing

# functions.py

def add(a, b): return a + b

def subtract(a, b): return a - b

def multiply(a, b): return a * b

def divide(a, b): return a / b

# call_functions.py

import functions

def main():

print(functions.add(5, 3))

print(functions.subtract(5, 3))

print(functions.multiply(5, 3))

print(functions.divide(5, 3))

if __name__ == "__main__":

main()

- Every Python module has a special built-in variable called

__name__.- When the module is run directly,

__name__is set to"__main__" - When the module is imported by another script, the

__name__variable is set to the module's name (without the.pyextension)

- When the module is run directly,

- This allows behavior to differ depending on whether the script is run directly or imported as a module.

# functions_test.py

import functions

import unittest

class TestFunctions(unittest.TestCase):

def test_add(self):

self.assertEqual(functions.add(5, 3), 8)

def test_subtract(self):

self.assertEqual(functions.subtract(5, 3), 2)

def test_multiply(self):

self.assertEqual(functions.multiply(5, 3), 15)

def test_divide(self):

self.assertEqual(functions.divide(12, 3), 4)

if __name__ == "__main__":

unittest.main() # runs all the methods with wrappers around them for debugging purposes

Equality & Identity

assertEqual(a, b)- values are equal (==)assertNotEqual(a, b)- values are not equalassertIs(a, b)- objects are identical (is)assertIsNot(a, b)- objects are not the sameassertIsNone(x)- value isNoneassertIsNotNone(x)- value is notNone

Boolean & Comparison

assertTrue(expr)- expression is TrueassertFalse(expr)- expression is FalseassertGreater(a, b)-a > bassertGreaterEqual(a, b)-a >= bassertLess(a, b)-a < bassertLessEqual(a, b)-a <= b

Membership & Sequence

assertIn(a, b)-ais in containerbassertNotIn(a, b)-ais not inbassertCountEqual(a, b)- have same elements, regardless of order

Type & Instance

assertIsInstance(obj, cls)- object is instance of classassertNotIsInstance(obj, cls)- object is not instance of class

Exceptions & Warnings

assertRaises(exc)— code inside block raises exception

with self.assertRaises(ValueError):

divide(10, 0)

Use the VS Code Testing panel

- VS Code has been configured to automatically recognize any file of the form test.py as containing

unittestobjects - Click on the flask icon in the VS Code sidebar to open the Testing panel

- Click on the play icon next to a unit test to run it, or else click on a play button higher up in the expansion to run them all.

- Break a unit test, test again, set breakpoint, and click on the Debug Test icon next to the test in the sidebar

VSCode is cool!

2025-10-13

Today's topics:

- Parsing data from stdin

- Python user-defined classes

- Doubly-Linked Lists (in Python, based on what we did in C)

remember, we use dummy elements for convenience (not performance)

- there is always an object to the left and right, so no NULL/None edge cases!

head tail

↓ ↓

[dummy] <-> [10] <-> [20] <-> [30] <-> [dummy]

Parsing data from stdin

import sys

def main():

# Read input from stdin and chomp the newline at the end

input = sys.stdin.read().strip()

# Split the input into a list of strings

number_str_list = input.split()

# Convert the list of strings into a list of integers

# Note: This is a list comprehension (more compact alternative to for loop)

numbers = [int(num) for num in number_str_list] # could even add an if clause at the end!

# Increment each number by 1

incremented_numbers = [num + 1 for num in numbers]

# Convert the list of integers into a list of strings

incremented_numbers_str_list = [str(num) for num in incremented_numbers]

# Join the list of strings into a single string with commas and spaces

print(', '.join(incremented_numbers_str_list))

if __name__ == "__main__":

main()

Node Class and Constructor Method

class Node:

def __init__(self, data):

self.data = data

self.next = None # equivalent to NULL pointer

self.next = None

# To instantiate:

some_node = Node(7) # self is a hidden parameter that is sent to Node.__init__

- "self" is a reference to the instance of the node that we are dealing with currently

- we don't actually have to name it "self", but that is convention and it would very confusing otherwise

Private and Public Methods

- In languages like C++ and Java, you can declare methods as being private (usually things like helper functions)

- means nothing except member functions of that class can call those methods

- Python doesn't have this ability

- we will use underscore to denote "private" methods (just convention, doesn't actually restrict usage)

Class DoublyLinkedList

- we will mirror the python built-in

listclass - abstraction: we will have same outer interface/function names, but implemented as a doubly linked list instead of a dynamic array

Constructor:

DoublyLinkedList()

Private:

_insert_after(node, data)

_pop_node(node)

Public:

append(data)

insert(index, data)

pop(index)

clear()

index(data)

Magic Methods:

supports print:

__str()__

supports emptiness check:

__bool()__

suports `in`:

__contains(data)__

supports for ... in:

__iter()__

__next()__

doubly_linked_list.py

class Node:

# Constructor for a node with data

def __init__(self, data):

self.data = data

self.next = None

self.prev = None

class DoublyLinkedList:

# Constructor for an empty list

def __init__(self):

self.head = Node(None)

self.tail = Node(None)

self.head.next = self.tail

self.tail.prev = self.head

# Used for __iter__ which supports the syntax: `for data in dll:`

self.iter_state = None # this is the current node that we point to while traversing

# Insert a new node after the given node

# This is a private method and should not be called directly from outside the class

def _insert_after(self, node, data):

new_node = Node(data)

new_node.next = node.next

new_node.prev = node

node.next.prev = new_node

node.next = new_node

# Remove the given node and return its data

# This is a private method and should not be called directly from outside the class

def _pop_node(self, node):

node.prev.next = node.next

node.next.prev = node.prev # note how we don't do any freeing! (automatic garbage collection)

return node.data

# Insert after the last node

def append(self, data):

self._insert_after(self.tail.prev, data)

# Insert before the node at the given index

def insert(self, index, data):

node = self.head

for _ in range(index):

if node == self.tail:

raise IndexError

node = node.next

self._insert_after(node, data)

# Remove and return the data of the node at the given index

def pop(self, index):

node = self.head.next

for _ in range(index):

if node == self.tail:

raise IndexError

node = node.next

return self._pop_node(node)

# Remove all nodes except head and tail

def clear(self):

self.head.next = self.tail

self.tail.prev = self.head

# Return the index of the first node with the given data

def index(self, data):

index = 0

node = self.head.next

while node != self.tail:

if node.data == data:

return index

index += 1

node = node.next

return -1

# Return a string representation of the list - supports `str(dll)`

def __str__(self):

return " ".join([str(d) for d in self])

# Return True if the list is not empty

# Supports the `if dll:` syntax to check if the list is not empty

def __bool__(self):

return self.head.next != self.tail

# Return True if the list contains a node with the given data (supports the syntax: data in dll)

def __contains__(self, data):

node = self.head.next

while node != self.tail:

if node.data == data:

return True

node = node.next

return False

# Initialize the iterator state (return self)

def __iter__(self):

self.iter_state = self.head.next # (our starting value)

return self

# Return the next data from the iterator and increment iterator

def __next__(self):

if self.iter_state == self.tail:

raise StopIteration

data = self.iter_state.data

self.iter_state = self.iter_state.next

return data

demo

- note how after we instantiate it, we use our doubly-linked list exactly like we would a usual list!

import doubly_linked_list as dll

lst = dll.DoublyLinkedList() # Create a doubly linked list

lst.append(1) # Append some data

lst.append(2)

lst.append(3)

lst.insert(1, 10) # Insert some data

d = lst.pop(1) # Pop some data

i = lst.index(3) # Find the index of some data

s = str(lst) # Get the string representation of the list

print(lst)

if lst: # Test if the list is empty

print("List is not empty")

if 3 in lst: # Test if the list contains some data

print("List contains 3")

if not 4 in lst:

print("List does not contain 4")

for data in lst: # Iterate over the list

print(data)

lst.clear() # Clear the list

if not lst: # Test if the list is empty

print("List is empty")